Insulation can keep a building comfortable while your walls quietly get wet. The way moisture, heat, and air move through an assembly determines whether the cavity stays dry or loads up with condensation over time. When builders compare faced vs unfaced insulation, the real decision is how each option supports the project’s moisture and vapor-control strategy rather than which label looks right on the packaging.

How Faced and Unfaced Insulation Perform in Real Projects

Every insulation choice must help maintain predictable moisture behavior inside the cavity while supporting the assembly’s thermal performance. Surrounding layers determine how vapor moves, how the wall dries during seasonal swings, and whether the sheathing ever reaches a temperature low enough for condensation. Under real conditions, the safest option is the one that keeps the enclosure stable through winter loads and summer humidity.

What Is Faced Insulation?

Faced insulation uses kraft paper or foil laminated to one side to control vapor moving from the warm interior into colder framing layers. That facer plays a defined role in cold climates where interior humidity routinely exceeds exterior levels during winter. Installers rely on the facer as a fastening surface to secure the batt without compressing it. Orientation matters on every job; if the facing points outward or sits beside another low-perm layer, moisture can become trapped with little chance to escape.

What Is Unfaced Insulation?

Unfaced insulation stays more vapor-open and depends on other layers for vapor control. Its thermal resistance does not change, but its drying behavior improves when vapor resistance already comes from interior coatings, smart vapor retarders, or exterior foam sheathing. In those assemblies, unfaced batts help maintain drying paths that shift with seasonal loads. Field crews see this most clearly in mixed or warm-humid climates where vapor can move in different directions throughout the year.

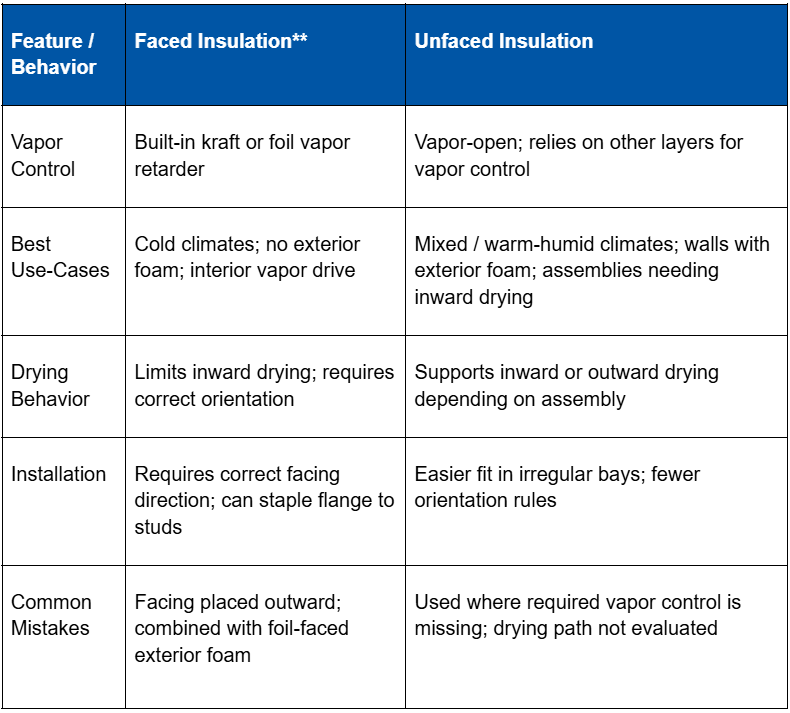

Faced vs. Unfaced Insulation at a Glance

**Cost and Installation Notes

Faced batts usually carry a slight cost premium because of the laminated kraft or foil layer and may take more time to install correctly, especially when aligning stapling flanges at each stud. Unfaced batts often install faster in irregular or tight framing bays and can simplify labor when other layers already manage vapor. Neither form changes the thermal resistance of the batt, but incorrect placement of a facing can lead to costly moisture issues that outweigh any labor or material savings.

How Continuous Insulation Changes the Faced vs Unfaced Insulation Decision

Continuous insulation has reshaped modern wall design more than any other single enclosure upgrade. Foam sheathing, whether foil-faced polyiso or certain forms of XPS insulation, keeps the sheathing warm through winter and limits condensation under load. When 3-inch polyiso insulation sits on the exterior side of the wall, the sheathing rarely encounters temperatures low enough to trigger moisture problems. In those conditions, unfaced batts on the interior prevent redundant vapor restrictions. Even so, when a wall lacks exterior foam and winter vapor pressures remain high, faced insulation helps maintain a controlled rate of diffusion toward colder layers.

Where Faced vs. Unfaced Insulation Matters Most

The same building-science principles apply across framing walls, attics, and below-grade spaces, but each application places different demands on vapor movement and drying paths. That is where faced vs unfaced insulation becomes a practical decision instead of a generic product preference.

Always confirm vapor-retarder placement with your local building code’s climate-zone requirements, since vapor-control logic shifts from heating-dominant to mixed and warm-humid regions.

Cold-Climate Framing Walls

On winter jobs, the kraft or foil facer slows vapor from reaching cold framing layers and cuts down the risk of condensation. Faced batts installed toward the conditioned interior manage diffusion as exterior temperatures fall. Where a wall has no exterior foam and interior humidity runs high, that facing becomes part of the primary vapor-control approach. Air sealing remains important, but the facing sets the diffusion rate.

Mixed and Warm-Humid Climates

Vapor drives reverse as seasons shift, and inward vapor loads can rise quickly when sun heats wet cladding. Unfaced batts protect inward drying when other materials already limit vapor flow, especially in assemblies that include exterior foam or reservoir claddings. In these climates, treating faced vs unfaced insulation as a climate-dependent decision, rather than a universal standard, helps maintain stable moisture levels inside the enclosure.

Vented and Unvented Attics

Above the ceiling plane, temperature extremes change rapidly, yet the principles stay consistent. In vented attics, faced batts installed toward the living space limit vapor flow into the attic so ventilation can remove what remains. In compact or unvented roof assemblies, rigid foam above the roof deck handles vapor and temperature, and interior batts are typically unfaced to keep the assembly from becoming overly restrictive.

Basements and Crawl Spaces

Below-grade walls introduce exterior groundwater and soil moisture as primary risks. When insulation sits on the interior side of a foundation wall, the choice between faced and unfaced batts must consider how the concrete will dry and whether a separate vapor barrier is already present. Many assemblies place rigid foam such as XPS or polyiso against concrete, then use unfaced batts in framed cavities so moisture is not trapped between impermeable layers. This is where improper facer placement leads to long-term dampness.

Common Installation Mistakes to Avoid

Cutting vapor movement in the wrong place can create new problems instead of solving old ones.

Incorrect Facing Orientation

Turning the kraft or foil side outward blocks drying and traps moisture where temperatures fall. In cold climates, the facing belongs toward the conditioned interior unless a specific design calls for a different configuration. The wrong orientation can undermine the projects entire moisture strategy.

Stacking Vapor Retarders

A faced batt behind foil-faced exterior foam forms a low-perm layer on both sides of the cavity, leaving moisture with nowhere to go. Trapped construction moisture or seasonal humidity can accumulate in the cavity and persist over time. That’s a common failure point in the field.

Copying Cold-Climate Details into Warm Regions

A facer that works well in a cold, dry climate can restrict necessary inward drying in warm, humid regions. When builders use cold-climate details in areas with inward vapor drives, the enclosure can accumulate moisture during rainy seasons. Matching the facing to the climate prevents these issues.

How to Think About Faced vs Unfaced Insulation in Real Assemblies

In practice, faced vs unfaced insulation comes down to where vapor resistance belongs, how the sheathing behaves under load, and whether the enclosure needs to dry inward or outward. Continuous insulation frequently shifts vapor control to the exterior, reducing the role of an interior facer. The safest choice is the one that keeps moisture levels predictable across the full range of seasonal temperature and humidity. That’s what keeps walls performing reliably.

Choose Rmax Continuous Insulation for Stable, Code-Compliant Moisture Control

Rmax continuous insulation systems help maintain stable sheathing temperatures and provide durable vapor control across a wide range of climates. These exterior layers coordinate with cavity insulation to support predictable drying paths and long-term enclosure performance. Contact us today for more information.